| Capitalism Accumulates Technological Truths  Dear Daily Prophecy Reader, Dear Daily Prophecy Reader,

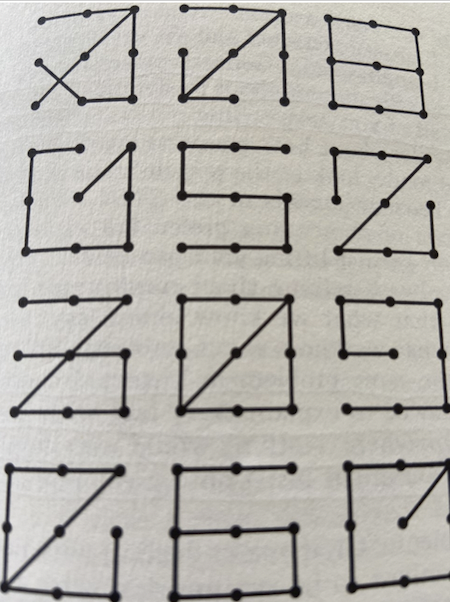

I’ve been traipsing around the country doing interviews, visiting the great John Schroeter of Moonshots, and Gilder Fellows zooming in Seattle. Diverting myself while I still can with cute dancing women on TikTok, or with Matt Ridley’s rousing new book on How Innovation Works, or with investors in California at 1517, and at Taylor-Frigon and its Israel strategy. I also enjoyed encountering my book, Life After Google, as a “business top seller” at the Amazon store near its Seattle headquarters. (See image below.)  I learned from all of my encounters — but as usual, most from Carver Mead — the visionary source of Moore’s Law, tunnel diodes, 25 new companies, and now a series of scintillating insights on physics. I’ll have his biography finished one of these years, but he keeps adding revelatory new chapters. Until then, for much of it, you can read Microcosmand The Silicon Eye. My favorite mode of thinking is analogy, or pattern matching. So all of my cerebrations on my trip led me back to an innovative book of dialogs on science by Robert Scott Root-Bernstein, Discovering: Inventing and Solving Problems at the Frontiers of Scientific Knowledge. It came up with an analogy of the discovery process consisting of nine dots in a box pattern that have to be connected to each other with lines. (See image below.)  Linking them with five lines is easy, yielding multiple solutions. Four lines, though, entails “thinking outside the box” coherently (the pencil need not leave the paper). Then to get three-line, two-line, one-line, and no line solutions requires radical changes in assumptions such as folding the paper like a protein, resorting to Riemannian geometry, and other extremities suggestive of Einstein’s general relativity: Throw away rigidities of the measuring stick and time. Time and space coordinates become elastic. Hey, that breaks the rules! Well, that’s rule number one, says Tom Peters, among other inspired simpletons, to enable truly new discoveries. Whether or not this analogy is seriously relevant to scientific progress, I have to report that it closely resembles the actual path of the one transistor memory cell in microchips. Thinking Outside the Box The industry began with six-transistor static random-access memories (SRAMS) with two flip-flops. Then it moved to four transistor dynamic RAMs, and then to three, two, and one transistor memory cells based on capacitors. It ended with the model inherited from the disk drive of the zero-transistor cell, consisting of a single magnetic domain, molecular memory, resistive, or phase change effect (Ovonic) device. The memory chip industry did have to think outside the box and then dissolve the box. Next come solutions to the memory problem of making memories that function at wire-speed as the wire crystallizes into fiber optic glass. These new approaches entail seeking “store width:’ moving the arrays of storage devices to datacenters and accessing them in massively parallel processes. In other words, breaking all the rules: that memories are supposed to be local and symmetrical and concentrated on particular microchips coupled to immediately reachable central processing units. Anyway, such analogies are fun to play with in this delightful book. But perhaps they fail to illuminate their subject very much. There is little entropy in this book, and what there is mistakenly identified as non-information — information as order, entropy as disorder. To imagine information is order rather than disorder is the great mistake made by many people, such as Ridley, who imagine they understand information theory too quickly. |

No comments:

Post a Comment