TradingTips.com |

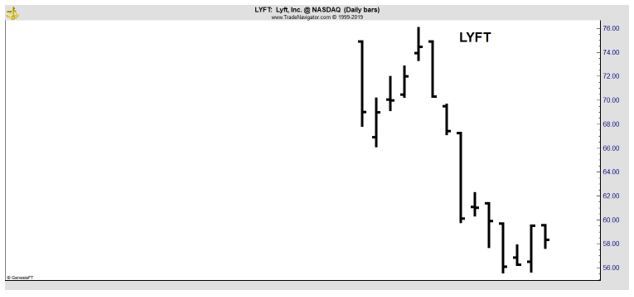

| Don’t Make These IPO and Trading Mistakes Posted: 25 Apr 2019 09:00 AM PDT Trading is challenging and it's difficult enough to succeed without facing additional problems created by mistakes. Yet, mistakes are possible and might even be common. For example, when there is an initial public offering (IPO) of a hot stock, the mistake could be buying shares of the company. The IPO of Lyft (Nasdaq: LYFT) demonstrates that the initial buyers of a stock could suffer quick losses.

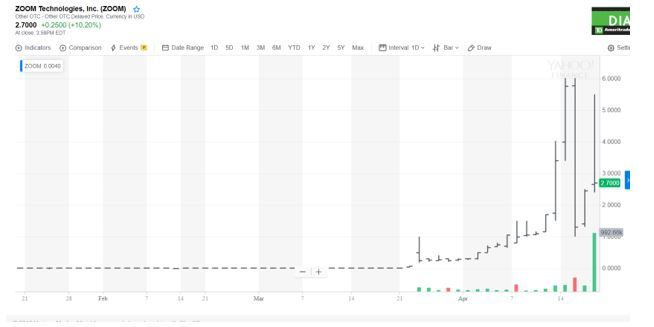

There is no assurance of a rapid rebound in these stocks. Snap (NYSE: SNAP) and Twitter (NYSE: TWTR), for example, are both below the IPO prices years after their IPOs. But there are other mistakes investors. One of the surprisingly common ones is buying the wrong stock. As Bloomberg recently reported, “Zoom Video Communications Inc. filed a draft prospectus for its initial public offering back on March 22. Yesterday it updated the prospectus with a marketing price range that could value the company, which provides a video conferencing platform, at more than $8 billion. Zoom will list on the Nasdaq Global Select Market under the ticker symbol ZM. ZM, you might notice, is not the optimal ticker. ZOOM would be a better ticker for a company named Zoom. ZOOM is taken. It is taken by a company called Zoom Technologies Inc. Zoom Technologies is not listed on the Nasdaq. It de-registered its stock in 2015; it still trades over the counter here and there, but not all that much, and not for all that much money. In February of this year, for instance, fewer than 5,000 shares of Zoom Technologies traded, according to Bloomberg data, at a high price of $0.004 per share, a low of $0.00 (what?), and an average of $0.0026. That is, about $12.32 worth of Zoom Technologies stock traded, total, in February, and its market capitalization peaked at $12,000. [Recently] Zoom Technologies closed at $1.00 per share, for a market cap of $3 million, up … infinity percent? … from its February lows. (Up 24,900 percent from its February highs, too.) Volume yesterday was 127,116 shares, or more than 1,000 times as many shares as traded in all of February. The price and volume started rising on March 22, the day that Zoom Video filed its prospectus, but things really got going in the following weeks. If you saw Zoom Video's prospectus filing, thought (incoherently!) "huh, Zoom is going public, I should buy some before that happens," and ran out and bought 1,000 shares of Zoom Technologies for $60, you are … well, "rich" is an exaggeration (you have $1,000), but your rate of return is excellent."

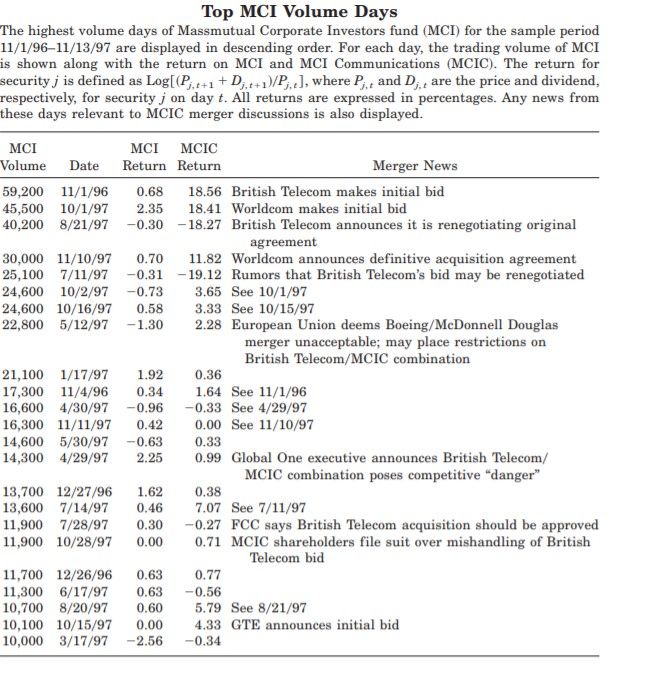

Source: Yahoo This isn't the first time this mistake happened. In 2014, The New York Times reported, "Nestor Inc. is a defunct shell of a company that once sold automated traffic enforcement equipment to state and local governments. Based in Providence, R.I., the company went into receivership in 2009, and all of its assets have been sold. Its shares, which are not listed on any exchange, have been dormant for years, worth less than a penny each. But on Tuesday, the stock woke suddenly from its long slumber to begin trading at one penny, jumping to a high of 10 cents a share. After a volatile day of trading, it closed at 4 cents. So, what happened? The price movement may be a case of mistaken identity stemming from an acquisition announced this week. Google said on Monday it had agreed to buy Nest Labs, which makes Internet-connected devices like thermostats and smoke alarms, for $3.2 billion in cash. Nest Labs is a private company based in Palo Alto, Calif. After the deal was announced, investors rushed to buy shares of Nestor, apparently confused by the company's ticker symbol, NEST. The stock continued trading on Wednesday, settling at about 4 cents a share by midday. This isn't the first time that a big deal on Wall Street has reverberated in the shadowy world of penny stocks. In October, after Twitter filed to go public, shares of Tweeter Home Entertainment — a defunct home entertainment retailer whose stock had barely traded — surged as much as 685 percent before trading was halted." In fact, the problem is so common, there's even an academic study on the subject in the Journal of Finance, Massively Confused Investors Making Conspicuously Ignorant Choices. This 2001 paper "examines the comovement of stocks with similar ticker symbols. For one such pair of firms, there is a significant correlation between returns, volume, and volatility at short frequencies. Deviations from "fundamental value" tend to be reversed with in several days, although there is some evidence that the return comovement persists for longer horizons. Arbitrageurs appear to be limited in their ability to eliminate these deviations from fundamentals." One example was the telecom company MCI.

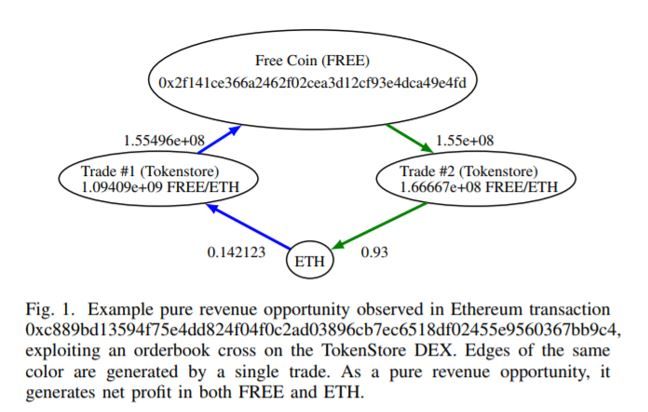

And, another example from Bloomberg: "Auris Medical Holding AG got a surprise boost to its stock price as investors mistakenly bought shares of the drug developer after Johnson & Johnson agreed to buy a similarly named robotics company for $3.4 billion. Auris Medical rose 9.4 percent at 10:40 a.m. in New York after earlier rising as much as 30 percent. Auris is a $13 million-ish market-cap hearing-loss-therapies company with the stock ticker EARS; about $5 million worth of its stock traded yesterday based on, by all indications, mistaken identity." The mistakes also happen in crypto markets as another recent study showed. In Flash Boys 2.0: Frontrunning, Transaction Reordering, and Consensus Instability in Decentralized Exchanges, the authors noted some investors have set up automated systems to take advantage of errors, typos on order entry in particular. One example is shown in the paper:

"Figure 1 shows one example of a pure revenue transaction, executed on November 15, 2018. In this transaction, two trades are executed on a decentralized exchange, TokenStore, which features a design conceptually similar to that of Etherdelta. The first executed trade buys Free Coin, an obscure token. By inspection, this difference in rates is a clear result of someone using the exchange API and committing an off-by-one error, offering to buy tokens at 10x the market rate. This created a cross in the order book (sell order at more than a buy order would pay), which when both executed by the same arbitrage counterparty, generates the flow of funds in Figure 1. While this opportunity probably arose from a typo, a variety of revenue sources exist. For example, inconsistent price feeds, or variance across exchange designs that respond to market movements at different speeds can also create pure revenue." The authors also found "[one trade], for example, appears to often profit off typographical errors users make in their decentralized exchange trades. One user, "Getcoin Hub Inc.", pleads with this arbitrage bot, saying "This was obviously a mistake transaction – any chance you can find it in your heart to send it back?". Another, Benjamin Huffman, pleads with the bot that "I am a single parent trying to make ends meet at a job I hate. Please have some mercy." Yet another, Alfie, leaves a comment requesting the return of their ETH, stating "Please I ask you to send me the ETH back as I really need it to continue my education. I might need to sell my car to pay what is already due for this semester." The lessons here are obvious: check your orders before sending it to your broker. Check for typos and be sure the symbol is what you think it is. There is no free money for individual investors and mistakes only provide free money to larger market makers. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| You are subscribed to email updates from TradingTips.com. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

No comments:

Post a Comment