Here’s Why Amazon Paid No Income Taxes for 2018

Posted: 28 Feb 2019 09:00 AM PST

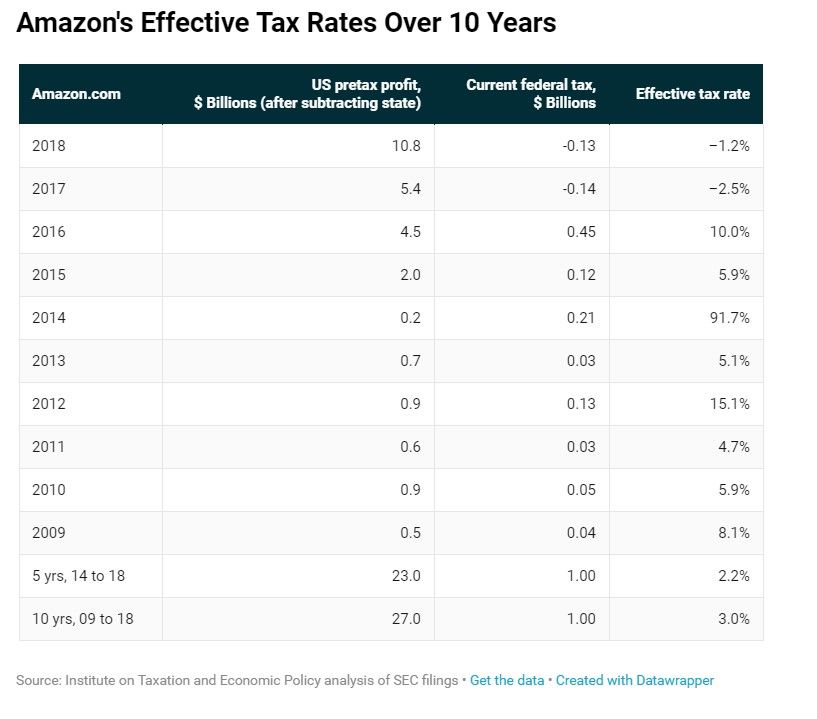

Amazon, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, "nearly doubled its profits to $11.2 billion in 2018 from $5.6 billion the previous year and, once again, didn't pay a single cent of federal income taxes.

The company's newest corporate filing reveals that, far from paying the statutory 21 percent income tax rate on its U.S. income in 2018, Amazon reported a federal income tax rebate of $129 million. For those who don't have a pocket calculator handy, that works out to a tax rate of negative 1 percent.

The fine print of Amazon's income tax disclosure shows that this achievement is partly due to various unspecified "tax credits" as well as a tax break for executive stock options.

This isn't the first year that the cyber-retailing giant has avoided federal taxes. Last year, the company paid no federal corporate income taxes on $5.6 billion in U.S. income.

Source: ITEP.org

Source: ITEP.orgITEP has examined the tax-paying habits of corporations for nearly 40 years and has long advocated for closing loopholes and special breaks that allow many profitable corporations to pay zero or single-digit effective tax rates.

When Congress in 2017 enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and substantially cut the statutory corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, proponents claimed the rate cut would incentivize better corporate citizenship.

However, the tax law failed to broaden the tax base or close a slew of tax loopholes that allow profitable companies to routinely avoid paying federal and state income taxes on almost half of their profits."

Are They Really Loopholes?

Many investors have asked how Amazon is able to pay so little in taxes. This is, of course, an important question. If Amazon is aggressively using tax rules that could highlight potential accounting issues that have been behind other company's rise and fall.

For example, according to the Guardian, "Enron, the US energy company that collapsed amid scandal in late 2001, evaded billions of dollars in tax with the help of “some of the nation’s finest” accountants, investment banks and lawyers, according to a report published yesterday.

The report delivered at a hearing in Washington found that Enron, once the seventh largest company in the US, paid no federal income tax between 1996 and 1999 and only token amounts in other years.

The three volume report was also critical of deferred compensation plans for executives used widely to avoid tax. It noted in passing that Enron had paid $53m (£32m) in previously deferred compensation to top executives in the weeks before it went bankrupt.

Charles Grassley, chairman of the senate finance committee, which commissioned the report, expressed outrage. Although there is no allegation that they stepped outside the law, he said it called into doubt the ethics of tax advisers and the “desperate” bankers, accountants and lawyers who worked with Enron."

But Amazon is not Enron. The company is generating cash from operations and has a valuable business.

So, how did Amazon limit the amount of taxes it paid? According to Vox.com:

"the interesting thing to note here is that Amazon isn't lowering its tax bill through classic technology company shenanigans like stashing profits in offshore subsidiaries or declaring itself to be a foreign company.

Amazon's sales are mostly in the United States, and its No. 2 market is Germany, which is also a relatively high tax jurisdiction.

Amazon isn't cheating anyone here; it just legitimately owes no taxes.

Some of that is because Amazon is able to avail itself of the research and development tax credit, a not-very-controversial policy that encourages profitable companies to plow earnings into R&D.

Congress routinely extends this on a bipartisan basis, with the thinking that research into innovation is good, and Amazon is obviously a company that does a fair amount of R&D.

The second reason is that the Trump tax bill included a temporary provision allowing companies to take a 100 percent tax deduction for investment in equipment. This is a controversial idea, but it has some support across party lines — Obama White House economist Jason Furman likes it, for example.

More broadly, when Democrats complain that companies are plowing too much of their profits into share buybacks rather than investing, they are in effect saying they wished more companies acted like Amazon — which does not do any share buybacks and does invest a lot — and this provision of the Trump tax bill encourages companies to do this.

Last and most significant to understanding the change in 2018 is the fact that companies can deduct the cost of stock-based compensation from their taxable earnings even though it doesn't actually cost companies any money to hand out shares of their own stock to employees.

What's more, the way this cost is estimated is that the more your share price rises, the bigger the deduction for handing out shares. So precisely because Amazon's profits surged, the price of the company's shares went up a lot and the value of these deductions surged as well.

That may sound a little unconventional — in general, the idea is that more successful firms should pay higher taxes, not lower — but there's a pretty good accounting reason for it. At the same time, the entire tendency of companies to offer executives stock-based compensation packages is essentially a giant loophole in a decades-old tax provision that was supposed to deter lavish executive compensation.

Stock-based compensation, explained:

Way back in 1993, Bill Clinton and congressional Democrats had an idea to tackle the growing pay inequality of Reagan-era America — Section 162(m) of the US Tax Code.

Normally, while companies pay sales taxes to state and local governments, the federal government taxes them on their profits. Revenue that is paid out to employees as salaries and benefits is not profits, and thus doesn't get taxed.

But section 162(m) created an exception to that rule — any salary of over $1 million paid to top executives would not be deductible for tax purposes. The idea was to deter lavish executive compensation packages.

Except there was an exception to the exception — compensation that took the form of stock options or stock grants would still be deductible. So in a practical sense, what the 1993 change did was incentivize companies to use a lot of stock-based compensation for their executives.

But here's a critical thing.

While a company of course could provide stock-based compensation by taking money out of the bank, using it to buy shares on the open market (this would be one of the dreaded share buybacks) and then giving those shares to executives, in practice, that's not how it works.

Amazon, or any other company, can just issue more shares of Amazon stock anytime it wants to. This costs Amazon shareholders in the sense that creating new shares tends to devalue the existing ones, but it doesn't involve any direct financial cost to the company per se."

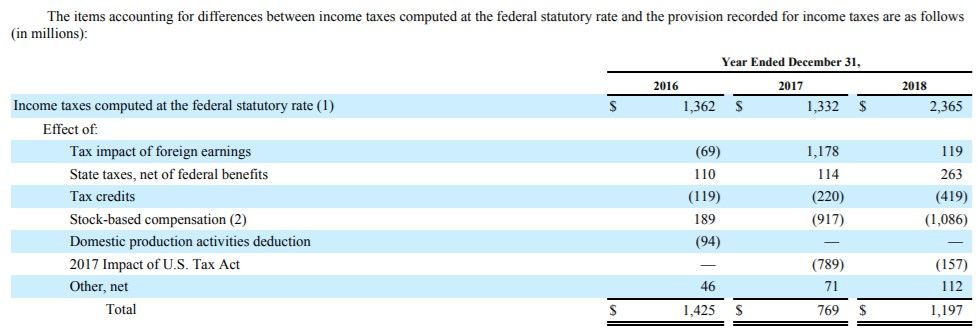

The chart below can explain the ideas.

Source: SEC

The company owed money based on income but the $1.1 billion deduction for stock based compensation offset that amount. The lesson for politicians is that any law, including one from 1993 designed to combat income inequality, can have unintended consequences.

If you are serious about trading, this is a must have right now. Click here for details.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now

You are subscribed to email updates from TradingTips.com.

To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now.

Email delivery powered by Google

Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States